In a remote area of southwest China, where walking on narrow paths remains the primary mode of transportation, the Nuosu people have made their home for more than one thousand years. Largely due to their isolation, they have managed to preserve their rich culture despite the Chinese government’s attempts to discourage all aspects of ethnic culture in the 1960s and 70s.

Curators Ma Erzi, Stevan Harrell, and Bamo Qubumo (from left) pose with mannequins clothed in Nuosu attire. The left mannequin is a bride whose black veil has silver adornments.

Fascinated by the Nuosu culture, UW Anthropology Professor Stevan Harrell has visited the region regularly since 1987. Now Harrell and his Nuosu colleagues Bamo Qubumo and Ma Erzi are offering the rest of us a glimpse of Nuosu culture through an exhibit at the Burke Museum of Natural History and Culture. “Mountain Patterns: The Survival of Nuosu Culture in China” runs through September 4.

Harrell explains that the Nuosu people are part of the Yi nationality, one of 56 nationalities in China. “I chose to study the Yi because there had been no outsiders studying them since the 1940s,” says Harrell. “And within the Yi nationality, I picked the Nuosu because there was a textbook of the Nuosu language.”

Harrell would need that textbook. Although he was already fluent in Chinese, the Nuosu have their own writing system and speak a language that few outsiders have learned. Fortunately, Harrell was rewarded for his efforts to learn the language, finding the Nuosu people “extremely friendly, straightforward, and welcoming.”

Nuosu women dance during a celebration in Liangshan, China.

There are approximately two million Nuosu living in China—four times the population of Seattle—yet little has been written about them. Nuosu people have traditionally been farmers and herders, living in isolated houses or small village clusters clinging to mountainsides. They build their dwellings out of whatever materials are available locally—wooden boards or planks, piled stones, or packed mud—with floors of packed dirt. “Throughout history,” says Harrell, “they have responded to their stark environment by evolving a rich material and spiritual culture in harmony with the harsh surroundings.”

It was while admiring objects from this rich culture that Harrell hatched the idea for the Burke exhibit. “Bamo Qubumo and her sisters were showing me things they had collected—mostly Nuosu clothing and textiles—and I thought, ‘We should do an exhibit in Seattle. People will find these things beautiful. And an exhibit could convey an important message about the revival of ethnic culture.’”

Harrell secured funding for the exhibit from the Blakemore Foundation of Seattle and the Asian Cultural Council of New York. Several UW sources also contributed, including the Simpson Center for the Humanities, the China Studies Program, and the Erna Gunther Fund of the Burke Museum. But the curators still faced one major hurdle: building the collection. “We had only five percent of the objects we needed,” Harrell recalls. “The next step was to collect.”

Silver Nuosu drinking vessels in the shape of doves.

For many exhibits, curators use existing collections or borrow them from collectors or museums. But few collections existed for Nuosu handiwork. Harrell and his colleagues acquired objects in Nuosu villages, often asking friends and neighbors whether they would like to sell traditional items from their homes.

“We were lucky with our timing,” says Bamo. “Nuosu don’t traditionally sell their things. But in the past two years, the situation has begun to change. People have become more open to the idea.” Bamo adds that Harrell’s reputation helped. “Our people call Steve ‘American hero,’” she explains. “So many of the people know him well. That helped us have good luck in our collecting.”

Not all of the items were easy to find. Bamo and Ma turned to Nuosu priests to locate scriptures and religious instruments. They also commissioned local artisans—silversmiths, lacquermakers—to create some traditional objects, although most items in the exhibit have been worn or used.

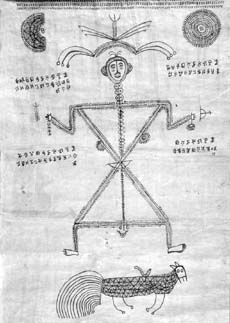

Priest paintings, such as this painting of a mythological hero on a horse, are used in Nuosu rituals.

By mid-1999 the group had collected or commissioned about 400 objects, most of which will become part of the Burke’s permanent collection. They include colorful Nuosu headdresses, men’s wide pants that resemble skirts, decorative purses, embroidered and appliqued textiles, silver jewelry, lacquerware bowls and plates, lacquered buffalo-hide armor, and many other items that reflect traditional Nuosu culture. The current exhibit includes about half of the collected items.

Harrell is thrilled that the public will finally have a chance to view the collection and discover Nuosu culture. “I feel a very deep connection to the Nuosu people and culture, even though I am an outsider,” he says. “I want that world to be available, in a sympathetic way, in the United States—especially in my hometown, Seattle. I think this exhibit is a good way to accomplish that.” Scanning the colorful collection, he adds, “We’ve collected hundreds of beautiful objects. Now we want to share them.”