"Horoscopes in Harmony are like the Clothes in an Outfit" says one of the beginning lines of a Nuosu Yi ritual text used to fix a rocky marriage. Among the Nuosu Yi people of the Liangshan region, in the mountains of southwestern

Sichuan, clothing and body decoration are media that express both social organization and cultural concepts. As the clothes in an outfit (and accompanying jewelry and hairstyles) harmonize with each other to express the aesthetic ideals of womanly beauty or manly bravery, so do different kinds of outfits form a visual code that says much about the social status of the wearer.

The Nuosu people are one of 30 or 40 closely related ethnolinguistic groups that were combined to form the Yi, one of the 56 minzu or "nationalities" into which China's population has been officially classified since the 1950s. Formerly known as Lolo, the Yi peoples now number almost 8 million, living in the southwestern Chinese provinces of Yunnan (4-1/2 million), Sichuan (2 million), Guizhou (1 million), and Guangxi (a few tens of thousands). The Yi languages, closely related but mutually unintelligible, form one branch of the Tibeto-Burman language family; many of these have their own writing systems, related to each other but not to Chinese, Tibetan, or any other extant scripts. Most of the Yi live in relatively mountainous regions, meaning that their styles of clothing are strongly influenced by the cool-to-cold climates and the availability of native materials in their home regions. The traditional female clothing styles of all the Yi peoples consist of a long, pleated skirt; a long-sleeved, decorated jacket; long hair worn in an elaborate headdress; and abundant jewelry mostly of silver; male styles include long pants of various cuts; jackets very similar to those worn by women;urban-style headdresses; and more modest amounts of jewelry than women typically wear. In this article, we illustrate the general forms and principles of Yi clothing by concentrating on the clothing and body ornamentation styles of the Nuosu, one of the Yi peoples least influenced by outside societies and cultures. The Nuosu live in the Liangshan, or Cool Mountain region of southwestern Sichuan, and in bordering areas in Yunnan; they number about two million today. They retain their own Nuosuhxo language in everyday use, and although traditional clothing styles for men are on their way out, women's clothing, especially that worn on special occasions, continues to build creatively and artistically upon traditions

of couture and dressing inherited from earlier times.

Environment and Society, and their Influence on Materials and Styles

The Liangshan, or Cool Mountains, are called that for a reason. Most parts of the Nuosu homeland lie at elevations of 1500 to 3200 meters above sea level, with the largest concentrations of population between 2000 and 2500 meters. At these altitudes, a primary function of clothing is warmth, especially in the long, dry, windy winter season. This is reflected in the fact that both sexes cover all of their body except hands, face, and feet; perhaps this has also led to notions of modesty that require such fully-covering dress on most occasions. In addition, the elaborate aesthetics and unique skills used to make woven and felted wool capes stem from the need for warm outerwear in the winter months. At the same time, the cold weather did not influence footgear; while straw sandals were known, many people used to go barefoot all winter long.

In addition, the relatively slow pace of cultural change in Liangshan can be attributed to the difficult terrain of the area. Range upon range of steep-sided mountains, dissected by deep, steep river gorges, made the area easily defensible against outsiders in premodern times. But difficulty of access also restricted the Nuosu to home-grown materials—such as wool, hemp, and leather—for everyday clothing, and made expensive trade goods—such as gold, silver, amber, and later imported cotton cloth and thread—into items of great aesthetic as well as economic value for clothing and jewelry.

There are also several social and cultural influences on clothing. One is the general cultural emphasis on bravery and martial prowess for young men, which has led to great elaboration of military clothing styles, including many kinds of

armor made of wood, rawhide, bone, and other materials; another is the complementary emphasis on beauty for young women, which has spurred on the crafts of the jeweler working in silver, gold, copper, and various inlay materials.

Clothing is far from incidental to Nuosu notions of cosmic, ecological, and social harmony.

Finally, perhaps partly because cold climates require more clothing, and thus provide a larger canvas upon which to work the aesthetics of fashion, Nuosu clothing in general is elaborate. An outfit has many pieces, including not just clothes but jewelry, carrying bags, and decorative collars and belts, and many items of bodily decoration are intricately patterned with needlework, fine smithery, or exquisite lacquer painting. Artisans, including those who manufacture clothing and jewelry, enjoy high status in Nuosu society, numbered along with rulers, ministers, priests, and mediators as one of the traditional categories of respected specialists.

Materials and Techniques of Clothing, Jewelry, and Armor Manufacture

"Women don't make felt; men don't weave cloth," says a Nuosu lurby, or parallel proverb. Cloth and felt are the two most common materials used in clothing, and there is a strict gender division of labor in their manufacture.

Spinning and Weaving. These household tasks are very important in women's lives. Skill at spinning and weaving is also an important standard for judging the worth of a woman. The long narrative poem Amohnisse, or "Mother's daughter" movingly describes the scene of spinning and weaving: "The black cape takes nine widths of cloth; the pleated skirt has a very fine weave. Daughter holds wool in her left hand; it looks exactly like white clouds. Daughter lifts the spun thread in her right hand; the spindle turns without stopping; the spun yarn stretches out straight. She spins with the speed of an

arrow leaving the bowstring; the coils of yarn flash like splashing hail..." The most important material for spinning and weaving is sheep's wool; in addition people spin small amounts of hemp and wild nettles.

Nuosu can shear and store up wool only during the yearly shearing season. When they weave, they spread it out and tear it very fine, or else use a bamboo bow to beat it to a downy consistency, rather like cotton wadding, and place it

into a little spinning basket woven of bamboo. They use a specially made spindle to spin it into a fine woolen yarn. They then twist two or three strands into a thread, which is used for weaving into woolen cloth.

Nuosu women produce woolen cloth in two different weaves: a plain weave and a twill weave. Home-woven woolen cloth is now used primarily for skirts and vala, or fringed capes [Figure 5]. To weave this cloth, a woman finds a flat place

inside the house or outdoors, and drives a wooden peg into the ground, about as thick as the bottom of a rice bowl. She ties one end of the warp yarn to the peg and the other to the weaving apparatus, which is held in front of the body,

anchored by a wide back-strap. This apparatus has no overall name in the Nuosuhxo language, perhaps because it is not a single loom, but rather a collection of tools that are brought together only by their connection with the thread and the cloth. She passes the woof yarn with the shuttle back and forth from left to right with both hands, and after each pass pulls hard with the wooden heddle to pack the woof tightly. [Figure 1]

Nuosu classify hemp into male and female, according to whether or not it produces flowers and seeds; this is an expression of the "gendered world" of the Yi peoples. Usually, the male hemp is harvested first with a knife; then a

wooden club is used to thresh it. The fibers are then peeled away, and it is rolled into hempen thread with two fibers to a strand. This is boiled in a wok for 10-12 hours, during which time wood ash is added and the mixture stirred; this helps

the cloth be tougher and more pliable. Then it is taken to the stream and pound-washed, after which it is soaked in oatmeal gruel for about an hour, which bleaches it out. This hempen yarn can then be woven into cloth, using basically

the same techniques used for wool. It is tough and durable, and was previously used to make skirts or female hygeine products.

Felting. Felting requires considerable skill, and is undertaken by males. But not every man knows how to do it; a family that needs felt products will hire a known felter. There are two kinds of felt capes: One is the unpleated, thick kind

known as wonbo; the other is thinner and has vertical pleats, and is known as jieshyr. The former kind can be worn at any time, and the quality of the wool is not too important; the latter is a kind of dress-up clothing, worn for gatherings or

when visiting. Felt is also used, over woven bamboo, in making conical hats.

For felting one needs to choose a windless, auspicious day, and first rip the wool apart and spread it out on a mat made of bamboo strips, according to the desired size, shape, and thickness, all the while beating it into wadding with the

fluffing bow. After this, the wadding is spread out evenly on the bamboo mat and sprinkled with a little hot water and the mat is rolled up into a cylinder. Two bamboo poles are inserted in the middle, and pulled by two people in opposite directions. When it is pulled tight, three muscular young men stand with one foot on the ground and use the other foot to roll the bamboo mat cylinder back and forth, pressing the wool inside the mat and causing it to stick together into felt. Then a woolen string is put through the collar as a drawstring, and the mat is rolled up and the cylinder rolled back and forth with the feet once again. After it is rinsed and dried in the sun, the wonbo or plain cape is complete. [Figure 2]

To finish a pleated cape or jieshyr, when the felt is taken out of the rolled cylinder, it is folded every three fingers' width and then pressed between two boards and tied up securely and stored vertically to allow the water to drain out.

After ten days or so it is dry, and when the press is opened the cape is complete.

Dyeing. Traditional Nuosu dyeing uses very ancient methods. The dyes, made from infusions of wild plants, produce only black, blue, and red. Black is made by boiling together horse mulberry and lacquer tree bark and leaves, and the filtered liquid is used to soak or steep the textiles, which are then rinsed in river water; the color is permanent and fast. Blue is made with a kind of tender shoots and leaves of a tree called kuoi, which are first sun-dried and then ground into a powder, which is rolled into cakes. For use in dyeing, the cakes are broken into pieces, and added to water with the leaves of the lacquer tree. Cloth is boiled in this mixture, and the resulting color is very fast. Red is made from a mixture of the leaves of the walnut tree and from powdered roots of a plant called vu. Textiles are boiled in this mixture two or three times. In more recent times, much Nuosu clothing has been made of brightly colored industrially-manufactured

cloth, which increases the possibilities for creativity on the part of seamstresses. But we still find traditional dyes, particularly the dark blue and black, used extensively in the manufacture of both cloth and felt capes.

Needlework. The beauty and attraction of Nuosu clothing is in the skilled and clever hands of Nuosu women. Nousu girls learn the arts of weaving, sewing,and needlework from their mothers and other village women; whoever has the best designed outfit, the outstanding embroidery patterns, will receive general praise as well as the attentions of young men. Many women know several different arts and many different patterns. Gems that dazzle the eyes include flying birds and running beasts, blowing clouds and running water, mountain flowers and wild grasses--every kind of natural wonder and scenic beauty--all concentrated in the arts of needlecraft and decoration. Men's and women's clothes--jackets and more recently vests, often worn over a purchased blouse or shirt-- both have needlework decorations on front panels, across the back, and on the sleeves. They use a great variety of techniques:

Couching: multicolored threads are braided, or cotton cloth cut into very thin strips, and then bent into all sorts of patterns, including windows, stairways, chains, waves, and pumpkins, and sewn onto the cloth.

Appliqué. Colored cloth is cut into repeating or duplicate patterns and sewn onto specific places in a garment, and the borders and corners outlined with colored thread or cloth strips, which are also used to embroider or cross-stitch around the seams; or silver plates and balls can be used for decoration. Names for patterns include sheep's horns, firelighter, waves, and many others.

Inset. Strips or tiny triangles of colored cloth, or lengths of embroidery thread are inset on the front panel of a jacket, or inserted into a border; the pattern is usually the coxcomb.

Edging. Colored cloth is used to edge the borders of garments, to give an effect of an uneven surface in order to bring out the colors more vividly.

Embroidery. Patterns are embroidered using colored silk thread, mostly in patterns of flowers, grasses, and leaves. This is very fine work, used most commonly on headcloths and sleeves.

Cross-stitching. Nuosu women use colored silk thread to cross-stitch many kinds of neat and intricate patterns, used mostly on collars and headcloths.

Jewelry

No Nuosu outfit, man's or woman's or even child's, is really complete without jewelry. Unlike the manufacture of clothing, which except for felt capes is a woman's art, jewelry is in the hands of specialist smiths, who are always male and often learn their art from their fathers and uncles in specialized clans. They work in a variety of materials, including gold, copper, amber, and various kinds of stones and shells, but their most characteristic and glorious medium is silver.

They manufacture both plain and fancy earrings [Figure 3], bracelets, rings, collar-buckles [Figure 5], buttons, and medallions for sewing onto clothing and collars. Most elaborate of all are the heavy bridal necklaces with intricate

patterns of birds, flowers, celestial bodies, and profuse tiny, conical chimes that make a subtle but alluring sound as the bride rides or is carried to her new home.

The fineness of Nuosu jewelry, and the expertise needed to make it, belies the crude circumstances in which ilversmiths ordinarily work; traditionally, and still sometimes today, they sit on a dirt floor beside a forge consisting of a simple tunnel under the floor, fired by wood or charcoal and fanned with a sheepskin bellows. Out of ingots of imported silver, they use tools they themselves make from iron and bronze to cold pound thin sheets, which can then be cut and bent into various sizes or stamped against a pitch board, either directly or repussé, into a variety of intricate designs. Or they use draw-plates, flat pieces of iron with different-sized circular holes, to transform long strips of pounded silver into fine wires that can be linked into tiny chains or braided and then soldered to thin metal sheets.

Rawhide armor

Until the large-scale import of firearms and ammunition began in the late 19th century, Nuosu wars and feuds were fought mostly with swords, spears, and bow and arrow. To defend against these weapons of offense there developed

protective armor that, like all other articles worn on the body, also developed its own aesthetic. Armor was almost always made of water-buffalo hide, and included body-armor consisting of a front and a back plate, each extending from the shoulders to the waist sewn together with leather thongs, and a short skirt made of several hundred overlapping rawhide plates, allowing for maximum mobility along with protection. These armor suits come in two styles; red background, or "male," and black-background, or "female", even though both are worn only by men. [Figure 4] On these backgrounds are painted elaborate patterns, closely related to the needlework patterns made by women. Their black, red, and yellow pigments are also used to decorate wooden or rawhide objects of daily use, such as bowls, tureens, serving dishes, and spoons. Similar patterns adorn other, now very rare, articles of armor, such as helmets, shin guards, and shields. Like smithery, manufacture of armor and other lacquerware was until recently the exclusive right of specialized clans.

Clothing and Social Status

For one who knows the code, it is easy to tell the social status of a Nuosu person in traditional dress just from looking. Men's and women's outfits have different components, of course, but many items, including every kind of cloth or felt cape and many sorts of hats, are true unisex clothing. A woman's basic outfit consists of headcloth or a hat; earrings—usually silver; a collar with a sliver buckle plate; a needleworked jacket or a vest over a blouse; a long, pleated skirt; and a hemp

belt from which hang a carrying bag, often a needlecase, and sometimes decorative tassels. She may wear rings or bracelets as additional jewelry, and if it is cold she will add a woven or felted cape. A man wears a turban, traditionally

enclosing a forelock of hair wrapped into a horn [Figure 2, left], a sliver earring in the left ear, a needleworked or plain jacket, long pants, and a shoulder bag. He may add rings on a few fingers, and in cold weather will wear a cape.

Traditionally straw sandals were distinctly optional for both sexes.

Some of the items that make up these outfits are the same for men and women, while others are different for the two sexes. In the Shynra and Yynuo areas, men's and women's jackets, though they are cut somewhat differently, use the

same kinds of embroidery patterns and are thus quite similar [Figures 1, 2, and 5]. And particularly in the Yynuo and Shama areas, men's pants, with wide legs and, in the Shama case, narrow pleats, are distinctly skirt-like in their appearance. But only men wear pants and only women wear skirts, and men's plain turbans contrast with women's elaborate and regionally distinct headgear [Figures 1, 3, and 5]. Women wear more jewelry than men; men traditionally

wore one small earring in the left ear, although some wore a heavy earring of amber and coral [Figure 2]; women wear earrings in both ears [Figures 1, 3, and 5], usually made of silver, and often long, dangly, and elaborate, swaying and

tinkling slightly as a woman walks. Women also are more likely to wear bracelets, though men sometimes wear simple copper ones, and only women wear the rectangular silver collar-clasps, or gie, that cause them to keep their head up while walking with the proud, striding gait valued by the Nuosu [Figure 5]. Both sexes wear silver rings [Figure 3], either plain or inset with various kinds of stone and bone, but it is considered unseemly for a man to wear more than two or three rings, while a woman can wear them on as many fingers as she likes or has rings for. Carrying bags are also different; though both are often lavishly decorated, men's bags are square and worn over the shoulder, while women's are triangular with long tassels, and hang from the belt.

Clothing also reflects the life-cycle, especially for females. Infants and small children have their distinctive hats, often appliquéd with fern patterns symbolizing growth, and in traditional times a young girl had a distinctive style of skirt, which she changed ceremonially for an adult woman's skirt at the age of 13, 15, or 17 years. At the same time, she may begin wearing her regional headdress. She continues to wear this style of dress through marriage, but when she gives birth to her first child, she will change her headcloth, or uofa for the corresponding regional style of hat, or uolur [Figures 1, 3, and 5], while wearing the same skirt, jacket, and jewelry. As she ages, she will gradually wear less and less bright colors, until as an old woman she will be dressed mainly in dark and neutral tones. At around age 50 she will make hers and her husband's funeral clothes and lay them away in wait for their cremation.

Each region and sub-region also has its own clothing styles. Ethnologists conventionally divide Liangshan into three regions according to the dialect spoken and the size of the men's pants. The Yynuo region in the northeast is also

called the big pants-cuffs region for the culottes worn by local men, Needlework is characterized by extensive use of bright oranges and reds, mostly in angular couched designs [Figure 1], Young women's headgear consists of several layers

of folded woolen cloth tied on top of the head by braids, and mothers wear a wide, black floppy hat sometimes called "lotus flower." The Shynra region [Figure 5] in the center and west of Liangshan is called middle pants-cuffs; the

most characteristic needlework on women's and men's jackets and vests is rounder in shape than in the Yynuo area, and features a combination of couching and intricate patterns of tiny inset cloth triangles. Young women wear a headcloth that hangs down in the back, often cross-stitched or embroidered; older women wear a square, black cloth draped over a rigid frame, sometimes edged in a single color. In the Ganluo sub-region much of the couching on jackets is replaced by embroidery, typically all in blues and greens. Skirts of both the Yynuo and Shynra regions feature a series of horizontal bands of different colors; they are finely pleated starting from the second band from the top. Clothing of the Suondi, or small pants-cuffs region in the south is quite different from the others [Figure 3]. Men's pants are fitted closely around the ankles, and their jackets feature braid and large silver buttons giving them a kind of "military band" look. Women's skirts of the Suondi are usually red and black wool, with only a few bands of other colors at the bottom, and pleats only in the lower, banded sections. Jackets, often worn in a long-short under-over combination, feature intricate patterns of appliqué, often in curly "cow's eye" or "ocean wave" designs and using the difficult technique of rolled or piped edges. The large,

circular, flat-topped hats worn by Suondi women [Figure 3] have largely disappeared at present, replaced on most ccasions by blue workers' caps inherited from the Communist Party cadres of the 1950s. Suondi women are known for wearing heavy jewelry, including earrings, bracelets, buttons, and rings to show off their families' wealth.

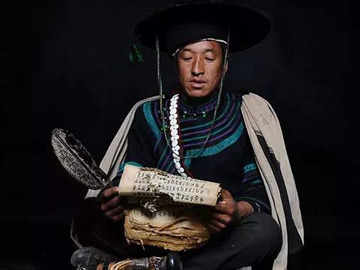

Finally, certain special social statuses are marked by clothing. Members of the aristocratic, or nuoho caste, called Black Yi in Chinese, often wore darker and more somber outfits than their commoner subjects. And the bimo, local priests

and custodians of ritual and natural knowledge and the Nuosu writing system, had elaborate conical bamboo hats topped with felt topknots and sometimes intricate finely-pounded silver plates; a bimo to this day must wear such a hat while performing a ritual, and others are not allowed to wear them.

Nuosu Clothing Today

Nuosu clothing has never been immune to outside influence--during the 18th and 19th centuries, for example, clothing in the area controlled by the Shama local ruler showed strong influence from surrounding Han Chinese people, and indirectly from the court costume of the Manchu Qing dynasty. But real changes began in the early 20th century, when brightly-colored yarns became available in trade and led to the elaboration of needlework patterns, while imported cotton

cloth became the favored material for skirts and allowed them to be much more colorful than previously; only on a few old women does one see traditional wool skirts in the muted colors of native dyes anymore.

Traditional men's clothing is now severely restricted in its use outside ritual and tourist contexts. Only middle-aged and older men, and not all of them, still wear any kind of turban, and very few grow the traditional forelock that used to be

wrapped in the "hero's horn" [Figure 2] that adorned the front of the turban. Similarly, traditional pants, of whatever cuff size, are rarely seen on anyone born after about 1940. By contrast, jackets with fancy needlework are still very common, produced in great numbers, and even young men often keep one for wear on festive occasions. One partial exception to the decline of men's traditional styles is among the bimo priests, who frequently still maintain elaborate traditional hairstyles and sometimes sport the heavy real- or fake- amber earrings. And they always wear their conical hats while performing rituals. Most of the time, however, the only articles of traditional clothing seen on Nuosu men are the fringed capes, or vala, which are ubiquitous in the winter, occasionally replaced by plain felt wonbo or pleated felt jieshyr. The common uniform is western-style trousers and a sport coat over an ordinary cotton or synthetic shirt; this is known as "Han clothing." Men do, however, still wear traditional-style rings, and although perhaps only a minority actually wear an earring most of the time, all boys have a pierced left ear, just in case.

Women's situation is very different. Only in urban areas have women basically given up their head-coverings; especially in cold months, even those who no longer wear the traditional headcloths or hats still sport brightly-colored wool scarves for warmth. Skirts vary from place to place. In some areas, particularly the western Shynra zone, most women wear skirts much of the time, and it is by no means a rare sight to see women digging potatoes, hauling firewood, or driving stock to market in brightly-colored skirts. Needleworked vests and jackets are also often everyday wear. On formal occasions, traditional clothing is expected, and a wedding, funeral, or holiday always presents a bright mosaic of banded skirts, needleworked jackets, elaborate headdresses, and swaying fringes of both men's and women's vala. But today, a purely traditional outfit is rare. Most women like to wear print-patterned blouses with their vests or jackets [Figure 5], and almost all of them wear some kind of pants—often warmup pants—under their full skirts. Only the poorest people in the most remote areas go barefoot anymore. And Nuosu clothing almost without exception has incorporated bright, industrially-produced chemical-dyed cloth and threads [Figures 1 and 5]; a recent and widespread innovation is to replace eedlework with store-bought, bright-colored and often sparkly rickrack. Women wear as much jewelry as ever, perhaps more now that living standards have risen somewhat in a few areas, making silver adornments more affordable; in ethnically mixed areas, the sartorial marker of Nuosu ethnicity on young women may be nothing but an embroidered vest and a pair of dangly silver earrings.

Children's traditional clothing, like men's, has become severely curtailed in its use. Traditional clothing takes time to anufacture, children grow out of things rapidly, and the use for hand-me-downs is not as great now that the official family planning policy restricts couples to three children. Skirts and vests still exist for little girls, but most girls do not begin earing Nuosu-style clothing, even on ceremonial occasions, until they are 12 or 13 years old. Boys sometimes have the traditional forelock, but otherwise are dressed like any other child from a poor village in China.

Since the 1990s, tourism and commercial cultural production have had a great impact on Nuosu clothing, as they have on clothing of all the Yi peoples. Tourist venues from urbran cultural performance theaters to villages that receive tour groups all require performers, greeters, and service personnel—male and female—to dress up in touristy, contemporary versions of traditional clothing. This is often known in Chinese as minzu fuzhuang, or "ethnic costume," and although the intent of the term is to imply that Han-Chinese attire (i.e. cosmopolitan or globalized fashion) is clothing, while what minority peoples wear is costume, in fact the term "costume" fits well with this kind of attire, worn to show off, for visitors, the ethnicity not just of the wearers but of the promoters of the activities and of the local population and culture. These "ethnic costumes" are generally extremely elaborate, make great use of shiny, synthetic fabrics and other brightly-colored elements, and combine with such imported innovations as makeup and high heels.

It appears then that the Nuosu, like so many peoples with distinctive traditional clothing styles, are subjected to contradictory pressures. The lures of the international market, of cheap and convenient clothing, and of global standards

of fashion and beauty are causing urban Nuosu, in particular, and increasingly rural people, to give up their ethnic styles in favor of a world aesthetic. But other factors promote ethnic clothing. Strong ethnic consciousness and a sense of

separateness from the Chinese mainstream, developing markets for tourism and ethnic art, and rising incomes that can be spent on luxury goods such as fancy clothes, all mean that traditional clothing is not just something that is being

displaced. It remains fertile ground for innovation and development of the skills and arts of manufacturing, designing, and wearing clothes and jewelry.

References and Further Reading

Stevan Harrell, Bamo Qubumo, and Ma Erzi. Mountain Patterns: The Survival of

Nuosu Culture in China. Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2000.

Zhong Dakun, Liangshan Yizu (The Yi of Liangshan). Beijing: Minzu Chubanshe,

1997.

Stevan Harrell

Bamo Qubumo